Bertino v Public Prosecutor's Office, Italy [2024] UKSC 9 (06 March 2024)

Citation:Bertino v Public Prosecutor's Office, Italy [2024] UKSC 9 (06 March 2024)

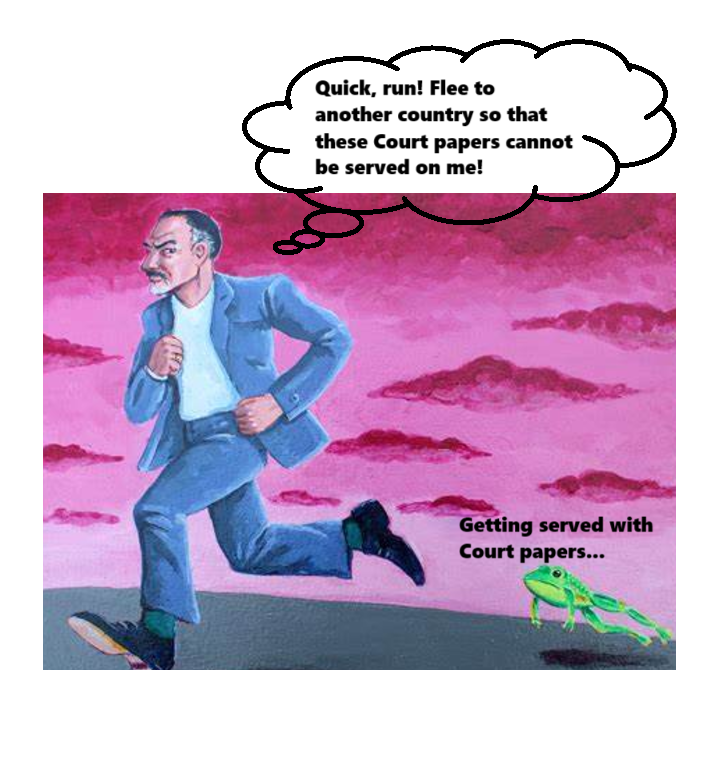

Rule of thumb: If you are told there is a criminal investigation started against you, so you flee to another country before you can be served with the trial date, but you are then found guilty in absence & sentenced, can you appeal that your Article 6 Right to a Fair Trial was violated? Yes, this is a valid loophole. If a person is informed of a criminal investigation, but not actually served with notice of the trial, so they are tried & convicted in absence, this is not an Article 6 compliant trial.

Background facts: This case invoked the subjects of procedural law & The Right to a Fair Trial.

The basic facts were that Mr Bertino was informed in Italy that he was under Police investigation. He then fled Italy to England. Bertino was sent correspondence to his Italian address informing him of a criminal trial. Bertino did not receive this as he was in England. The trial went ahead & Bertino was found guilty and given a lengthy custodial prison sentence. Bertino appealed that his Article 6 Right to a Fair Trial was violated.

Court held: The Court upheld Bertino’s arguments. If a person is only served with notice of a Police investigation likely to lead to a Court trial, but not actually served with Court trial proceedings properly so that they cannot attend the trial, then any Judgment is a violation of Article 6. In criminal proceedings, this means that a country must use the extradition process if necessary to inform people of a trial, or else any Judgment will not be valid.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘58. The certified question on this issue poses a choice in black and white terms: "For a requested person to have deliberately absented himself from trial for the purpose of section 20(3) of the Extradition Act 2003, must the requesting authority prove that he had actual knowledge that he could be convicted and sentenced in absentia?"

59. The Strasbourg Court has been careful not to present the issue in such stark terms although ordinarily it would be expected that the requesting authority must prove that the requested person had actual knowledge that he could be convicted and sentenced in absentia. As we have already indicted, in Sejdovic at para 99 (see para 38 above), on which Miss Malcolm KC relied, the court was careful to leave open the precise boundaries of behaviour that would support a conclusion that the right to be present at trial had been unequivocally waived. The cases we have cited provide many examples where the Strasbourg Court has decided that a particular indicator does not itself support that conclusion. But behaviour of an extreme enough form might support a finding of unequivocal waiver even if an accused cannot be shown to have had actual knowledge that the trial would proceed in absence. It may be that the key to the question is in the examples given in Sejdovic at para 99. The court recognised the possibility that the facts might provide an unequivocal indication that the accused is aware of the existence of the criminal proceedings against him and of the nature and the cause of the accusation and does not intend to take part in the trial or wishes to escape prosecution. Examples given were where the accused states publicly or in writing an intention not to respond to summonses of which he has become aware; or succeeds in evading an attempted arrest; or when materials are brought to the attention of the authorities which unequivocally show that he is aware of the proceedings pending against him and of the charges he faces. This points towards circumstances which demonstrate that when accused persons put themselves beyond the jurisdiction of the prosecuting and judicial authorities in a knowing and intelligent way with the result that for practical purposes a trial with them present would not be possible, they may be taken to appreciate that a trial in absence is the only option. But such considerations do not arise in this appeal, where the facts are far removed from unequivocal waiver in a knowing and intelligent way.

Conclusion The appellant did not unequivocally waive his right to be present at his trial. For the purposes of section 20(3) of the 2003 Act he was not deliberately absent from his trial. With respect, we conclude that the district judge and Swift J erred in coming to the contrary conclusion. The question should have been decided differently. In the result we would allow the appeal and, pursuant to section 33(3) of the 2003 Act, order the appellant's discharge and quash the order for his extradition’.

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.